A journey into the Indonesian rainforest in search of Rafflesia arnoldii, the world’s largest and rarest bloom, hidden deep in Indonesia.

I have always loved plants, but there was one that lingered in my imagination more than any other, a flower so rare and immense that it seemed less like botany and more like quiet legend. Rafflesia arnoldii, the largest flower in the world. This was one bloom I longed to see for myself.

I was told she could be found deep within the rainforests of Indonesia, in Sumatra and parts of Borneo, hidden beneath thick canopy and tangled vines. The journey would not be simple. To find her, I would need patience, and an experienced Indonesian guide who knew how to read the forest floor with care and understanding.

RAINFOREST TRAIL

TROPICAL JUNGLE

LOCAL GUIDES

Before dawn one humid morning in the heart of the Sumatran rainforest, I followed a narrow game trail behind such a guide, his eyes scanning the moss-covered earth as if searching for a subtle sign. We were not tracking an animal, nor listening for the snap of branches, but searching for something rarer still, a flower that blooms so infrequently and so briefly that many speak of it with reverence.

The forest felt attentive. Leaves glistened in the early light. Vines hung heavy in the damp air. In that hushed expectancy, I felt as though we were waiting for something extraordinary, yet entirely natural.

Rafflesia is unlike any flower I have known. She bears no visible stems. No leaves reach for sunlight. No roots anchor her into soil. Instead, she lives quietly as a parasite within the woody vines of Tetrastigma, drawing sustenance unseen from her host until, months later, a swollen bud begins to form.

UNOPENED RAFFLESIA BUD

That bud develops slowly, sometimes over six to nine months before revealing herself in astonishing scale. When fully open, she can measure up to a metre across and weigh as much as eleven kilograms. Five thick lobes unfold outward, deep red to burnt orange in colour, each patterned with pale, wart-like markings that appear almost deliberate in design.

And then there is her scent.

To ensure survival, Rafflesia emits a powerful odour of decaying flesh, a smell strong enough to carry through still air. It attracts flies and other insects, her essential pollinators, earning her the nickname “corpse flower.” As I stood waiting in the undergrowth, I wondered quietly whether we would sense her presence before we ever saw her.

Her bloom is fleeting. Three days, perhaps seven if conditions allow. Then the petals darken, soften, and return to the forest floor. Such scale. Such anticipation. Such brevity.

FULL RAFFLESIA BLOOM

The first recorded Western sighting was in 1818, though long before that, local communities knew of her existence. Even now, while she may appear at various times of year, peak blooming often coincides with the wet season, when the rainforest is at its most saturated and alive.

Though birds do not pollinate the flower, some forest birds and tree shrews are known to feed on the fruit, helping disperse seeds and continue her hidden cycle.

Standing there in filtered green light, I understood something that measurements alone cannot explain. Rafflesia does not bloom for admiration. She opens whether witnessed or not. She draws strength quietly, appears briefly in grandeur, and then yields once more to the forest.

To search for Rafflesia is to accept that you may not find her. But perhaps that is part of her quiet lesson, that not all wonders reveal themselves on demand. Some require patience. Some ask for humility. Some wait in the dark.

And when they do appear, they remind us that the rainforest still holds secrets beyond our understanding.

Editor’s Note

During my travels through Indonesia, I have often been drawn to what lies just beyond immediate sight, the quieter, less obvious wonders of the forest. This story reflects that search and the patience it requires.

Kat.

Written with deep respect for the forests and the lives it shelters.

At first light, before the heat settled heavily over the fields, I watched women step quietly between rows of corn. Their hands moved with a familiarity that spoke of generations, checking husks, lifting woven baskets, brushing soil from tender shoots. In many parts of Indonesia, it is women who carry a significant share of the labour that brings food from earth to table.

Corn ripened under careful watch. Nearby, vegetables and fruits flourished, fiery red chillies, leafy kale, crisp lettuce, fragrant parsley and celery. In season, durian hung heavy in the trees, and snake fruit rested beneath its russet, scaled skin. Much of this produce supported household income, travelling from small family plots to local markets where I would later see the same women weighing, bargaining, and smiling across wooden stalls.

CORN FIELDS

HARVESTING CHILLIES

HARVESTING LETTUCE

SELLING CORN, SOME ROASTED ON SMALL FIRE

AN ABUNDANCE OF FRESHLY PICKED VEGETABLES AND FRUIT

TRADITIONAL MARKET IN LOMBOK

FIERY RED CHILLIES

VEGETABLE MARKET SURABAYA INDONESIA

DRAGON FRUIT

SALAK ALSO KNOWN AS SNAKE FRUIT

Along the coasts, I saw another rhythm entirely. At low tide, women waded into clear shallows to tend delicate lines of seaweed strung between wooden stakes. Seedlings were tied carefully by hand. Later, the harvest was gathered and spread out beneath the sun, turning stretches of shoreline into quiet mosaics of green and gold. Seaweed farming had become an important livelihood, particularly in times when rural incomes felt uncertain.

SEAWEED HARVEST INDONESIA

WOMEN GATHER SEAWEED AT NUSA PENIDA INDONESIA

WOMEN DRYING SEAWEED AT NUSA PENIDA INDONESIA

Inland, diversified agriculture was also taking root. Some women were training in agroforestry, cultivating cocoa beneath taller shade trees or producing palm sugar from carefully tapped trunks. Others drew upon long-held knowledge of leaves, roots, and bark to create organic remedies. Their contribution reached beyond physical labour. I was often told how women participated in decisions about planting cycles, crop sales, and household spending, shaping both harvest and home.

COCOA FRUIT

COCOA BEANS DRYING ON ROADSIDE

COCOA PODS, BEANS AND NIBS

Their days, however, were long. As primary caregivers and managers of household subsistence, women carried added responsibility when challenges arose. If water had to be brought in, they organised and carried it. If illness touched the family, they adapted and tended quietly. Their work stretched across field, shoreline, kitchen, and cradle.

What remained with me most was not hardship, but steadiness. A quiet dignity. A sense that soil, water, and tree canopy were not separate from their own wellbeing. These women worked with deep respect for the forest and the lives it shelters.

In the quiet industry of their days, they sustained more than crops. They sustained continuity of land, of knowledge, of family.

Editor’s note:

During my travels through Indonesia, I was continually struck by the steady presence of women in fields, markets, and coastal farms. This story is a reflection of those observations, written with deep respect for the forest and the lives it shelters.

Kat.

Photo by huynhkhoa

Somewhere in the deep Indonesian jungle hangs a treasure, not buried in the earth, but suspended in the high green silence of the canopy.

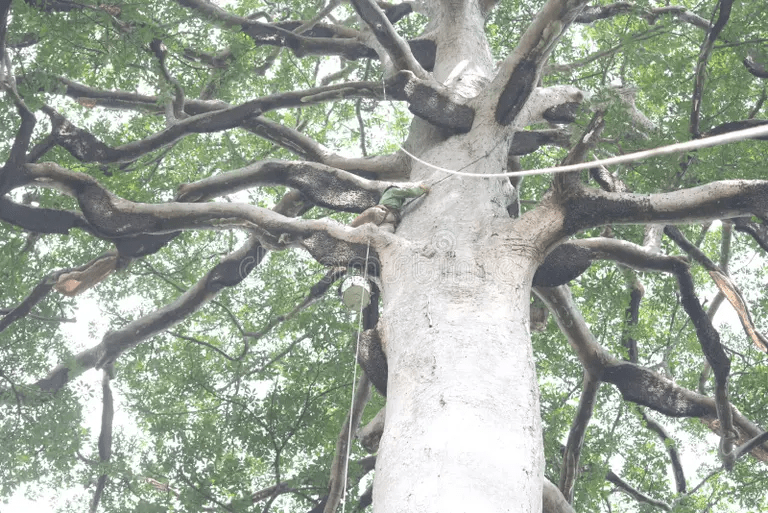

From towering trees known locally as Sialang, the giant honeybee, Apis dorsata, builds vast crescent shaped hives that cling to the highest branches like burnished shields. At certain times of year, when the forest blooms and the honey thickens in the heat, men gather at the base of these trees and prepare to climb.

I lived in Indonesia long enough to taste this honey often. We would order three litres at a time. It arrived dark, almost black, dense and opaque, never overly sweet. It tasted of rain soaked bark and hidden wildflowers. It was raw and unfiltered, sometimes clouded with pollen and flecks of wax. Over time it crystallised naturally, turning from liquid amber to something creamy and grainy, still carrying the scent of the jungle.

Photo by Stefan Schweihofer

The jungle from verandah

Kingfisher seen from verandah

In places harvesting follows ancient rhythms. The traditional method, known as Menumbai, takes place during the dry season when flowering is abundant and the hives are heavy with nectar.

But the sweetness comes at a cost.

At dusk, or under a moon thinned by cloud, a small fire is lit at the base of the tree. Smoke coils upward, softening the air and easing the fury of wings. Then the climber begins, barefoot, gripping bark worn smooth by generations before him, ascending into a darkness alive with sound. Hand woven rope ladders sway against the trunk. Long bamboo poles reach into the canopy.

The bees sting. The female workers defend their colony fiercely, sacrificing their lives if their barbed stingers embed in skin. Yet the men climb steadily. For many families, wild honey is not a luxury; it is a primary source of seasonal income. In some regions it accounts for more than half a household’s cash earnings.

Still, they do not take everything.

Part of the hive is always left intact so the colony can rebuild. The tree itself is protected under customary law. No one cuts down a Sialang. In some communities, disputes must be settled before entering the forest. Rituals are performed. The bees are spoken of as little forest princesses. Harvesting is not extraction, it is relationship.

Across Indonesia, from Sumatra to Kalimantan and east toward West Timor, wild honey depends entirely on healthy forest ecosystems. In the mountainous forests annual harvests are still guided by inherited knowledge passed from elder to youth, rope by rope, knot by knot. In parts of Borneo, structures known as tiking or man made wooden trunks, encourage wild bees to nest without domesticating them, working with instinct rather than against it.

Even beyond bees, the forest guards its sweetness. In arid regions, honeypot ants sometimes called living pantries, store nectar within their swollen bodies to sustain their colonies through scarcity. Harvested carefully by Indigenous communities, they offer another reminder that in these landscapes, survival and sweetness are intertwined.

Replete honepot ants with nectar filled abdomens, living storage units for their colony.

This honey is not gathered in hives, but held in their bodies, a different kind of honey, born of adaptation and survival.

Wild honey is often called liquid gold, valued for its rich flavour and reputed medicinal qualities, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and restorative. It is exported across Indonesia and beyond. Yet its truest worth may be quieter.

As long as the bees require tall trees, the standing jungle holds more value. A living tree dripping with honey is worth more.

I never tasted the pale spring honeys of Indonesia, only the dark forest harvests. Thick, smoky, complex. To this day, it remains one of the finest honeys I have ever eaten.

And when I think of it now, I do not first taste sweetness.

I see a man climbing into the night, guided by ancestral memory, trusting the forest to give, and disciplined enough to leave part of it’s gift behind.

For the forests that still stand, and the hands that climb with care.

Arrival in Indonesia can feel overwhelming.

The heat is thick and humid, jungle pressing close to villages, roads rough and unpredictable. Traffic appears to follow rules known only to locals. Vehicles overtake into oncoming traffic without hesitation, squeezing past one another with astonishing precision. No anger, no panic just an unspoken understanding that everyone will make it through.

It feels unfamiliar. Foreign. Slightly chaotic.

And then, slowly, something else becomes noticeable.

People greet me with easy smiles, often placing a hand to their chest with a small bow of the head. The gesture is subtle but meaningful. Respect seems woven into daily life, for elders, teachers, and religious leaders. Voices are generally soft, movements restrained. Even in busy places, there is a quiet consideration for others.

I notice small moments. A shopkeeper patiently helping an elderly customer. A young person lowering their gaze when speaking to an older relative. Kindness expressed without display.

Many people tell me younger Indonesians are changing slowly. Global culture arrives through films, television, music, and social media. Romantic language feels more familiar now, yet family expectations remain strong. In places like Java, even language itself carries levels of formality, reinforcing respect and social harmony.

Public emotional restraint is deeply ingrained. Behaviour that might cause embarrassment to oneself or to others, is generally avoided. Love, I’m told, is not usually shown through words or touch. It is shown through action.

Food is provided. Favours are done quietly. Loyalty is steady. Responsibility toward family is carried without complaint.

Locals are curious and kind. They ask where I’m from, whether I need help, or if I would like to buy something. These conversations feel warm, sometimes shy, always generous. Connection is offered, never imposed.

Gradually, a realisation forms.

Affection exists here, simply expressed differently.

I don’t see families hugging as I’m used to at home, nor couples openly displaying romance. Strong emotion, especially romantic emotion, is often kept private. Not because feelings are absent, but because self-control is valued. Many people grew up without being hugged or kissed by their parents, rarely seeing open affection between adults. Love was understood rather than spoken, something restrained until marriage.

It’s no surprise, then, that many young people say they learn about romance from movies, TV dramas, K-pop, and social media rather than from home.

Emotion here is not suppressed, it is redirected. Joy and humour are freely shared. Grief is communal. Anger is discouraged in public. Romantic longing is held inward.

And then there are the cats.

They are everywhere, roaming freely, fed by communities, tolerated and often gently adored. In a culture where restraint is valued, affection toward animals becomes a visible and acceptable outlet. It is quiet, compassionate, and uncomplicated.

For me, this becomes the lesson.

To travel well in Indonesia is to observe before acting, to listen before interpreting. What feels normal through a Western lens can sometimes be misunderstood here. Respect is not loud, but it is constant.

To some travellers, Indonesian behaviour may seem reserved or hard to read. But beneath that restraint lies deep loyalty, strong family bonds, and relationships built to last.

Affection here is shown through presence, duty, and consistency, not always seen, but deeply felt.

Written with respect for the forests and the lives they shelter

This year begins with attention. I enter it aware that writing is not a destination, but a practice one shaped by curiosity, patience, and a willingness to listen.

I do not begin with answers. I begin with questions, with observation, and with a commitment to stay present to what unfolds. These pieces will be shaped by revision, reflection, and the understanding that meaning often emerges slowly.

What follows is part of an ongoing journey. I offer this work in the spirit of exploration, trusting that clarity will come not from haste, but from care.

Kat

My stories focus on the people of the islands of Indonesia, how they live, how they survive in the jungle, and the work that shapes their daily lives. I am drawn to places where life is lived close to the land, and to the often unseen relationships between people, animals, and environment.

Animals are an integral part of these stories, particularly cats, the affection many communities have for their local cats, and the way domestic animals coexist alongside larger wild jungle cats and other wildlife. These relationships speak to a wider ethic of coexistence, one that asks for attention, respect, and compassion toward all living beings.

Through travel and presence, I seek to bear witness rather than explain, allowing stories to emerge from observation and lived experience. I am especially interested in out-of-the-way places and everyday lives that are rarely centred, believing that widening our circles of compassion begins with listening closely.

I hope to connect with free-spirited travellers and writers who are curious about local cultures and willing to look beyond familiar paths. Above all, I aim to share stories that offer insight into Sumatra and other parts of Indonesia, its people, their resilience, and the quiet wisdom found in simpler ways of living.

Kat.

This year has been one of quiet exploration. Through writing, revising, and returning to ideas that mattered to me, I found myself paying closer attention to language, to nature, and to the stories that ask to be told gently rather than loudly.

Some of these pieces began as questions rather than answers. Others emerged from curiosity, concern, or a simple need to bear witness. What connects them is a growing understanding that writing is not about perfection, but about presence, staying with an idea long enough for it to reveal its shape.

This work reflects where I have been in 2025, learning, refining, and allowing my voice to deepen with time. I share it in the hope that it invites the reader to pause, reflect, and perhaps listen a little more closely to the world we share.

Kat

For now, hope still walks softly through the jungle. Whether it endures depends on what we choose to protect.

Powerful yet rarely seen, the tiger is a creature of silence and patience.

Confirming new life in the wild is never easy. Tigresses are intensely protective mothers, keeping their cubs hidden for many months. The forest itself becomes their shelter, concealing the smallest paws beneath thick undergrowth. Often, young cubs remain unseen, their existence known only through subtle signs, a distant call, a fleeting shadow, a brief image captured in the quiet of night.

The absence of sightings does not mean the absence of life. In the forest, much happens beyond human view.

Encouragingly, observations from remote jungle regions suggest that in some areas where forests remain intact, tiger numbers appear stable. When natural habitats are undisturbed and prey is plentiful, the forest continues its ancient rhythms.

New life has also been welcomed in carefully managed wildlife environments, where planned breeding programs help safeguard genetic diversity. Recently, two tiger cubs were born under human care, small, striped bundles of strength and instinct. Their arrival brought quiet celebration and renewed hope.

Their father had once been injured and later recovered under supervision. Their mother was born within the same protected environment. Together, they represent continuity, a reminder that with care and patience, life endures.

Across Asia, the tiger has long symbolised courage, strength, and protection. For centuries, it has appeared in art, folklore, and storytelling, not only as a predator, but as a guardian spirit of the forest. Its presence has always stirred human imagination.

Yet beyond symbolism, the tiger is simply what it has always been: a solitary hunter, moving through dense vegetation, perfectly adapted to its surroundings. It needs space, food, water, and quiet territory in which to roam.

When forests remain whole, balance is possible.

Each cub born, whether hidden deep in the wild or nurtured in managed care, represents renewal. Survival is not dramatic. It is gradual. It unfolds quietly beneath the canopy, one generation at a time.

The future of the tiger rests not in grand gestures, but in steady protection of natural landscapes. Where forests stand, life continues.

In the humid stillness of the jungle, where filtered light falls across leaf litter and unseen creatures move through shadow, hope still walks softly.

Whether it continues to do so depends on the space we allow the wild to remain wild.

Written with respect for the forest and the lives it shelters.

This island was her last kingdom. Since the injured tiger returned to the wild, the forest has kept her secrets. No human eye has witnessed her cubs beneath the leaves. But hope remains. It always does in the jungle. Only the unblinking eye of a camera may one day reveal a flicker of stripes in the night, proof that life continues where silence reigns. Elsewhere, life unfolded in different forms.

Under gentle human care, a tigress gave birth to her cubs. The first arrived quietly, small, blind, and roaring with life. Months later, a second followed. Two fragile beginnings, stepping softly into the world. Names and ceremonies faded into memory; what mattered was the rhythm of life, continuing quietly beneath the canopy.

Their father had once been injured and had endured hardship. He survived, carrying scars that whispered of resilience. Through him, the future breathed again.

Caught by a silent camera

With the birth of the cubs, the sanctuary became a haven, a place where life could continue, protected, nurtured, and watched with care. Humans, too, could be guardians, not only observers.

Beyond the fences, in the remote jungle where rain hammered the leaves and shadows shifted silently, signs of renewal emerged. Camera traps captured fleeting images of striped ghosts moving through the dark. In protected places, the forest whispered of life continuing, slow, uncertain, but real.

The tiger’s world is one of patience and quiet strength. Mothers hide their young, teaching them the rhythms of the forest. Cubs grow strong among the leaves and vines, their stripes darkening, claws sharpening against the earth. Life unfolds in moments often unseen by human eyes.

The jungle endures. Somewhere in the depths of the island, the older tiger moves silently through ferns and shadow. Somewhere else, two cubs grow stronger, learning the ways of the wild. The story of these tigers is not written in headlines or statistics, but in the quiet persistence of life, the continuation of generations, and the resilience of the forest itself.

For now, the last tigers of this island still breathe beneath the trees, moving through shadows, teaching us patience, hope, and reverence.

Written with respect for the forest and the lives it shelters.

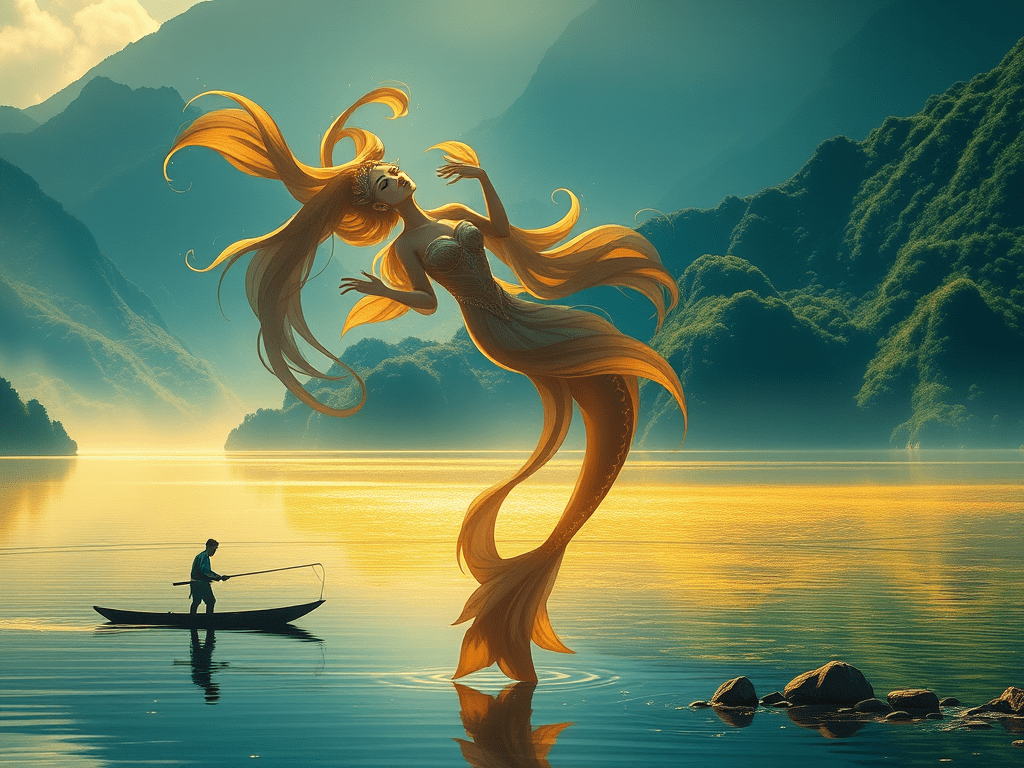

Nestled high in the heart of North Sumatra, there is a place so breathtaking it feels like a dream, called Lake Toba. Surrounded by a protective ring of emerald mountains, the lake stretches endlessly, shimmering like polished glass under the changing sky, the largest and most beautiful lake in Indonesia.

The air here is cool and crisp, even in the warmth of the afternoon sun. Time slows down, and there is a hush to the world as though the mountains are holding their breath, guarding something sacred. The lake lies still, but there is something about it, something haunting, something eternal.

To stand by its edge is to feel something stir inside you. A sense of wonder, longing you can’t quite name.

Because Lake Toba was not always just a lake, it was once the setting of a love so deep, so powerful, and a betrayal so tragic that it changed the course of nature itself.

Here is the story of how it all began.

A story of a man, a woman, and a secret that would ripple through generations, like waves across the water.

Each morning, just as the first light spilt over the mountains, the fisherman walked alone, quiet, with weathered hands and kind eyes that had grown used to solitude. As he cast his net into the still waters with little expectation, save for the simple hope of enough fish to carry him through another day.

But that morning was different.

The sky was soft with early morning light, and the lake shimmered like liquid gold. As the fisherman pulled in his net, suddenly he saw a golden fish, unlike anything he’d ever seen. The scales sparkled like sunlight on water, luminous and surreal, as though they had drifted in from another world.

He reached for it gently, almost reverently, just as his hands closed around it, something extraordinary happened.

“Please do not hurt me,” said the fish, with a voice soft, melodic, filled with sorrow and something ancient.

“I’m not truly a fish,” the voice continued, “but a woman cursed long ago.”

He stared in disbelief, heart pounding. Then, without a sound, the shimmering body in his hands began to change. Brightness swirled around her, warm and blinding, and in a heartbeat, she was there.

The fisherman froze.

A woman.

Radiant, ethereal, with eyes that held the depth of centuries of sadness that reached into his soul. Hair falling in waves like the water around them, and her presence was both fragile and powerful, like something out of a forgotten dream.

He had never seen anyone so beautiful. Though neither of them knew it yet, from that moment on, everything would change.

She smiled at him, her eyes soft with gratitude. “Because you showed me kindness,” she said gently, “I’m free now. I could stay with you, and we could make a happy life together. He listened, completely still, as her voice lowered into something almost fragile. “Promise you won’t tell anyone I was a fish.”

And they began their life together. It was simple, but it was real. A small house built by hand, a garden where they planted vegetables, and the sound of shared laughter echoing through the days. Joy in the little things, in morning coffee, hands dirtied by soil, quiet glances that said more than words ever could.

Then came their child, a beautiful boy, with bright eyes and a laugh that filled the room like sunshine. He was interested in many thangs, clever, wonderfully mischievous, chased butterflies, sometimes forgot his chores, but had a good heart, and his parents loved him very much.

Years passed in the blink of an eye. Then one day, everything changed.

The fisherman returned home late, weary to the bone. The sun had been merciless, the work harder than usual, and he had waited, hungry and aching, for the lunch his son had forgotten to bring. Frustration rose like a wave inside him, and before he could stop himself, the words tumbled out.

“Lazy boy! You are nothing but the child of a fish!”

The words hung in the air like shattered glass. Time stopped.

The wind fell still, the trees stood frozen, and the light dimmed, as though the world itself had heard. And she had heard too.

From the doorway, the woman he had loved beyond reason stood silent. Her eyes, once filled with warmth, were now wide with hurt. And behind them, a deep, ancient sadness had returned, like something that had only been sleeping all these years.

He knew, in that instant, what he had done and that he could never take it back.

Tears welled in her eyes, soft, shimmering, and full of sorrow. She stood still for a long moment, looking at the man she had once trusted with her secret, the man she had built a life with.

Her voice was barely more than a whisper, but it carried the weight of everything they had shared. “You promised, and now the secret is broken.” The pain in her eyes was not anger, it was deeper than that. It was heartbreak.

She knelt, gathered her little boy in her arms, and held him close. There was a gentleness in her touch, even as her heart broke in two. “I need you to know who I truly am,” she said softly. “I was once something else, and the magic that kept me here is now gone.”

She kissed his forehead one last time, and then, like the last breath of a dream at dawn, she vanished.

The sky darkened almost instantly, turning a cold, ominous grey. Thunder cracked like a broken heart across the mountains, and rain poured down in torrents, as if the heavens themselves were grieving. Rivers rose violently, breaking their banks, and the ground trembled with the force of something far greater than man.

The fisherman ran outside, shouting her name into the wind, desperate to turn back time. But it was too late.

Water surged into the valley, swallowing fields, trees and houses. He watched helplessly as the world he knew disappeared beneath the rising flood. All was gone except for one hill, the place where their home had once stood.

That hill, now quiet and alone, remained above the water, and it became an island, still, serene, and breathtaking in the very heart of the vast lake that had formed Lake Toba.

And so, from one act of kindness, a secret, and a single broken promise, the world was given one of its most beautiful lakes.

But for those who visit, if you listen closely to the wind, you might still hear the whisper of love lost, and a promise that was once made under the mountain sky.

Written with respect for the forest and the lives it shelters.